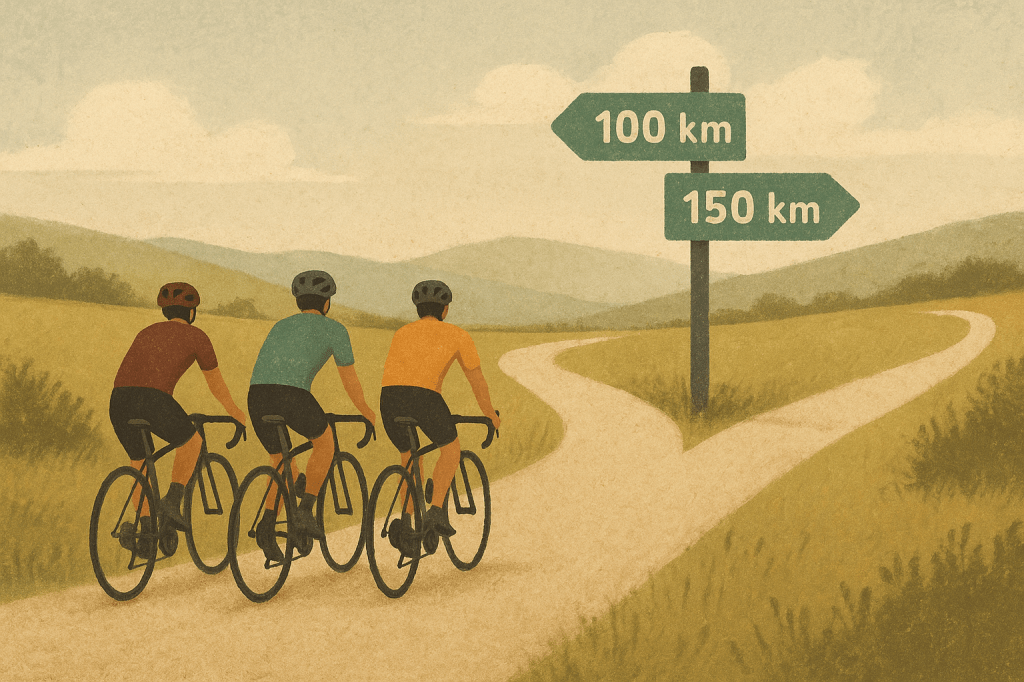

In less than two days, I’ll be on the start line for the 150km sportive. There are two routes that day — 100km or 150km — and at the 35km mark, just after the first big climb, there’s a junction. Turn left and it’s the shorter route. Turn right and it’s the full thing. That choice feels like the whole ride in miniature: test the legs, listen to the head, and then decide whether I’ve got what it takes to go the distance.

I’m excited, a bit nervous about riding in such a big group, but I know from experience that it thins out quickly enough. What sits with me more is whether the work I’ve done this year is the right kind of work. I haven’t ridden over 100k in three weeks, but the last one I did was 121k. The rowing and strength work mean I’m heavier now, but heavier in the right way: stronger, more resilient. I can leg press 150kg these days, not bad for someone who struggled with 70 when I started measuring this in March 2025. The endurance rows have kept the engine ticking too, even when the weather kept me indoors.

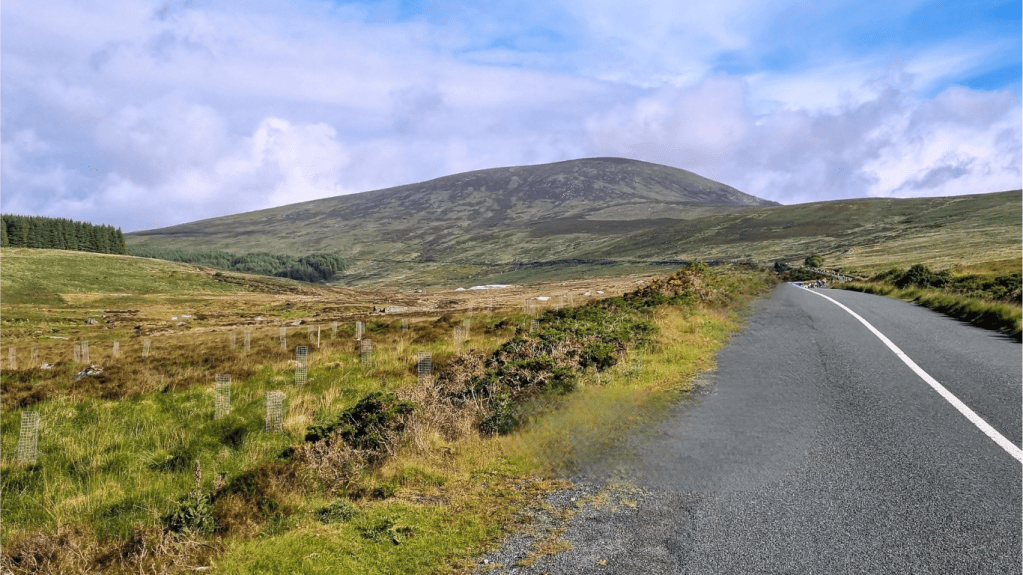

The bike has been through its own transformation this year. Lighter wheels, better gearing, and most recently new gel pads and handlebar tape that have taken the sting out of the Irish roads. It’s not set up for rain, no mudguards, but this is Ireland, rain is part of the deal. Still, I’ll be riding with a piece of both my parents: the bike bought with a little money from Mum when she passed, and the saddle from Dad for my birthday. That matters more than any component choice.

Success on the day is simple: finish strong without grinding myself into the ground, enjoy the company of my friends, and carry the memory with me. If the legs aren’t there and I have to turn left at the junction, then so be it. If something mechanical forces me to stop, then I’ll still have had a weekend away with good people. But if the legs are there, and the head is steady, then turning right — taking on the full 150 — will be the real win.

This ride isn’t part of the Sub-7 Experiment, not really. Different training, different demands. But it is part of the bigger experiment: how to keep moving, how to choose things that are mine, how to remember that age hasn’t caught me yet. This is one of the rare things I do just for myself, away from family. And yet, finishing it well at 55 is also a reminder of what I bring back to them: proof that I can still do hard things, still choose adventure, still find joy in movement.

The road will be long, but I won’t ride it alone.

This is the Sub-7 Experiment and this weekend I am mostly riding a bike.